John Hawkins was a wealthy land owner and merchant. Before the Revolution, he served as commissary under a Virginia State Commission. From the start of the Revolutionary War until his temporary retirement in 1777, Hawkins was the main supplier of food and durable goods for Virginia troops. Hawkins’s retirement from the army was announced in the Virginia Gazette on March 7, 1777.

A Poor State Of Supplies In Virginia

By the spring of 1778, Governor Patrick Henry was exasperated by the poor state of supplies for the Virginia line of the Continental Army, and he was determined to persuade his old friend, John Hawkins, to return to public service as Commissary for Virginia for the Continental Army. Henry argued forcefully to convince Congress to appoint Hawkins to the position:

“I exerted all my personal influence,” Henry told R. H. Lee of his effort to get an old Hanover friend, John Hawkins, to take on the commissariat in Virginia; if Congress failed to approve the arrangement, it could not count on any more help from Henry. The congressional delegates, stung by Henry’s uncharacteristic vehemence, secured a host of departmental reforms that brought some relief by spring.”

Congress agreed to Hawkins’s nomination in the early spring of 1778. The first record of Hawkins’s appointment appeared in the Virginia Gazette on April 3, 1778. The notice, signed by Governor Henry, reads:

“Since publiſhing the above, by advice of the Council, I have employed Mr. John Hawkins of Hanover County to collect beef and bacon for the grand army. All perſons who can furniſh either of theſe articles are requeſted to inform the ſaid Hawkins, or some of his agents thereof. Informations reſpecting this buſineſs coming to me from the County Lieutenants, or others, will be ſpeedily ſent to him. I do once more earneſtly recommend this important matter to all ranks of people in the ſtate. [Signed] P. HENRY”

Governor Henry announced the appointment of Hawkins in the following speech to the Virginia House of Delegates on 13 May 1778:

“The situation of the grand Army with respect to provisions has been so alarming, as to threaten no less than the final dispersion of it. The letters from Congress and General Washington, while they imported this, called for every possible aid from this state. The most vigorous and proper measures the Executive power could devise have been pursued. Mr. John Hawkins has been appointed purchasing Commissary, and to him and sundry others employed before him occasionally, very large sums have been advanced. Congress have been informed of the whole matter, approved of what has been done, and promise to refund the money speedily.”

Hawkins was instrumental in saving the desperately under-supplied army at Valley Forge: To the genius and exertion of Hawkins during the short time he lived after his appointment to the Commissary Department by the Board of War, much was also due. That gentleman had displayed in the discharge of his duties the most indefatigable activity. Nature and observation had fitted him for that sphere of usefulness; his mind pervaded the whole State, and the effect of his services outlives him. He died in Richmond in 1779.

Hawkins died of a smallpox inoculation just 2 months after his appointment as Commissary. However, his efforts were felt to have had a lasting beneficial effect for the war effort. The year following Hawkins’s death, Thomas Jefferson wrote the following to Patrick Henry, in a letter dated March 27, 1779:

“I am mistaken, if, for the animal sub-sistence of the troops hitherto, we are not principally indebted to the genius and exertions of Hawkins, during the very short time he lived after his appointment to that department, by your board. His eye immediately pervaded the whole state; it was reduced at once to a regular machine, to a system, and the whole put into movement and animation by the fiat of a comprehensive mind.”

John Hawkins’s service in the Continental Army was brief but productive. His story has been under-appreciated by history, in part because of the paucity of colonial records that survive from Hanover County, and in part because it appears that Hawkins did not seek public attention or political office. Except for his will, not a single document survives in his own voice. We are left to speculate that this was a man who was comfortable and content in private life, but willing to answer his country’s call to service with industry, skill, and the courage to risk his life.

John Hawkins: Smallpox Inoculation And The Continental Army

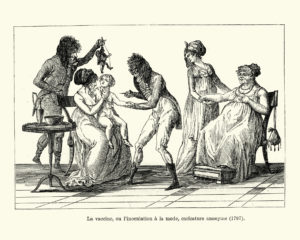

A few weeks after joining the Continental Army as Commissary for Virginia, John Hawkins underwent the dangerous procedure of smallpox inoculation, as was required of all soldiers and officers in the Army in 1778. Hawkins died as a result of the procedure.

England: Where Smallpox Vaccinations Began

True vaccination against smallpox did not begin until 1796 when Edward Jenner first used the cowpox virus to induce immunity to smallpox in a young boy in England. Before that time, a dangerous procedure called “inoculation” was used to induce immunity: actual infected material from a patient with smallpox was inoculated under the skin of a healthy individual. They would actually develop smallpox, but the death rate from this controlled infection was 1-2%, as opposed to up to 40% if the disease was contracted in the community.

Inoculation was dangerous, but not just because of the 1-2% death rate. More importantly, the inoculated individual was infectious for several weeks and could start an outbreak of the disease in his family and community. For this reason, inoculation was illegal in most of Colonial America, including Virginia; only in Pennsylvania was inoculation entirely legal.

Inoculation was forbidden by general orders for all officers and soldiers in the Continental Army as late as 1776, although Washington was ambivalent.

Washington’s Take On Inoculations

By 1777, Washington felt compelled to decide in favor of inoculation for the entire Continental Army. British soldiers were mostly immune to smallpox, due to frequent outbreaks of the disease in England. In contrast, smallpox outbreaks had been rare in the Colonies, and American soldiers were highly susceptible to the disease. In fact, Washington’s siege of Quebec on December 31, 1775, failed mainly because smallpox ravaged the American troops.

On January 6, 1777, General Washington issued an order commanding that American troops, then camped at Morristown, New Jersey, be inoculated with smallpox. The one-page order, taken in dictation by the young Alexander Hamilton and signed by General Washington, is currently on view at Mount Vernon. The result of Washington’s order, as he anticipated, was a miserable winter, with rampant smallpox infection, and some number of deaths. However, his strategy worked: By spring, most troops had recovered and were now immune to the disease. From that time on, the Americans continued a vigorous inoculation program for all soldiers and officers of the Continental Army.

Gov. Patrick Henry Recruits John Hawkins

Governor Patrick Henry recruited John Hawkins for the Continental Army in March 1778. Hawkins underwent the required inoculation procedure a few weeks later. We can assume that he remade his will on April 21, 1778, because he understood the risk he was taking. His will opens:

“In the name of God amen. I John Hawkins of Hanover County having been lastly inoculated for the small pox and finding it convenient to make some alterations in the will that I have by me do make and with my own hand write this my last Will and Testament…”

The risk of smallpox inoculation was greater for a man of 60 years of age than for younger men, and in fact, Hawkins succumbed to the disease. We presume that Hawkins had died by or soon after June 2, 1778, when his replacement was first recorded:

“Colonel Richard Morris… On 3 June 1778 he was named in place of John Hawkins as purchaser of provisions for the Continental Army.”

© 2013 W. Mullins